By Invitation: Xi Jinping's response to complex challenges - China's 14th 5-year plan on the way

Insightview.eu has invited Joergen Delman, professor, PhD, China Studies, Department of Cross-Cultural and Regional Studies, University of Copenhagen, to write about China's 14th 5-year plan covering the period from 2021 to 2025. The plan will also have significant implications for European companies with exposure to the Chinese economy.

Joergen Delman works on China’s political economy, politics, civil society, climate policies and environmental issues. He is a frequent public speaker and media commentator on these topics and has lived in China for ten years, working as a consultant for international development organisations, as well as Danish and international businesses. He has worked extensively with and within Chinese government organisations at central and local level. Joergen Delman is Co-coordinator of ThinkChina.dk.

China’s new 14th five-year plan [FYP] covering the period from 2021 to 2025 is a key tool to attain the long term goals for China’s development. The final plan will only be disclosed at the annual session of the National People’s Congress [NPC] in March next. However, before then, the

upcoming 5th plenary meeting of the Central Committee [CC] of the Chinese Communist Party [CPC], to be held in late October, will endorse the draft after having analyzed the current economic situation and the results of the 13th five-year plan.

While little is known about the specifics of the 14th FYP at this stage, there have been some sneak views into the planning process, the guiding philosophy of the plan, some of its overall targets, and some of its sectoral concerns. At this stage, three main priorities seem to be emerging: The need to uphold vigorous economic growth rates, a focus on enhancing economic independence of the US, defined as economic security, and a green turn of the economy.

Development philosophy

The FYP is an important moment in China’s policy cycle. The planning process takes years and involves hundreds of organizations around China, including research institutes and think tanks that are asked to provide inputs to the plan. Formally, the plan is a guidance document and not legally binding. Only a few key quantitative targets will be mentioned and subsequently translated into hard targets for local administrations down the vertical lines of the party-state bureaucracy. Still, the FYP is critical to provide policy guidance across all major policy agendas. It is considered the ‘mother’ of all other plans, i.e. tens of thousands of regional and sector plans that must translate the overall policy framework into local political action.

The planning process was taken over by the top leadership in November last, and the National Development and Reform Commission [

NDRC] is responsible for the final collation of the five-year plan.

CPC General Secretary,

Xi Jinping’s

New Era thinking, which has been enshrined in the Party and state constitutions, serves as the overall guide for the plan. Within this framework, Xi defined

two ‘centennial’ development goals. The first was to "build a moderately prosperous society in all respects" in 2021 when the

CPC celebrates its 100th anniversary. More specifically, Xi proposed an "income-doubling" goal that aimed, first, at doubling the GDP per capita income of both urban and rural residents by 2021 in comparison with 2010 levels.

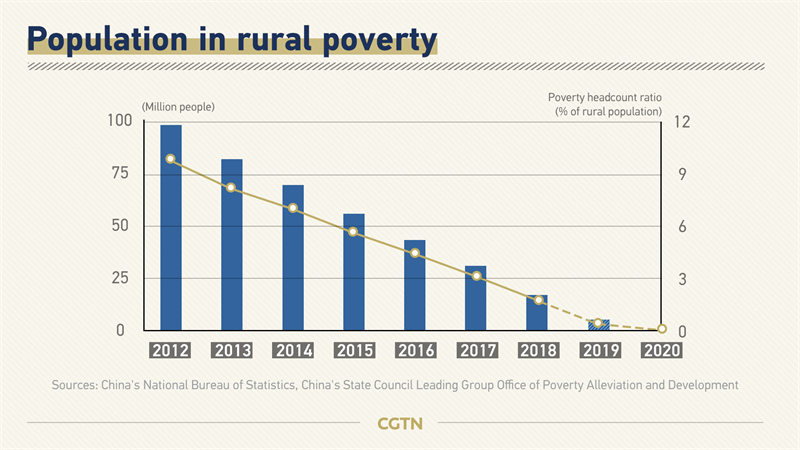

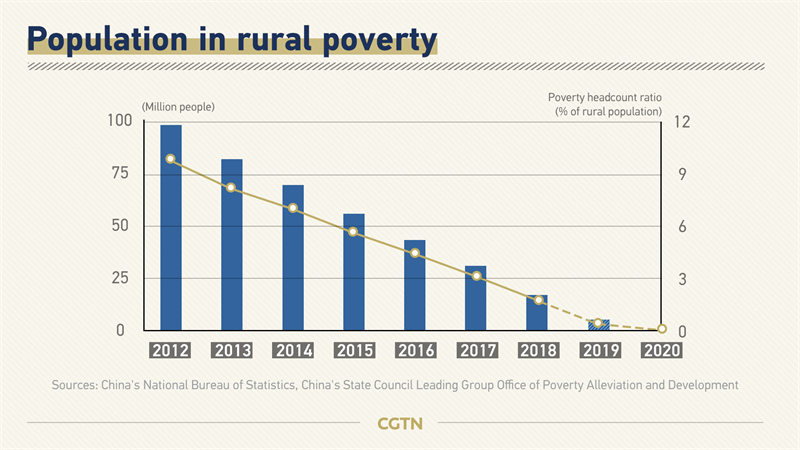

According to official sources, this has already been achieved. In additions to this, Xi also wanted to lift the rest of China’s 16-17 million inhabitants living on $1.90 or less per day out of poverty before 2021. This target is also expected to be fulfilled this year. [The

official Chinese statistics reflected in the figure below show how China will end poverty in 2020.]

Incidentally, this poverty alleviation effort also explains some of the

Draconian policies to modernize Xinjiang and Tibet in recent years through forced internment of local “minorities”, indoctrination, skills upgrading and group transfer of rural surplus labour to industry and services.

Xi’s second centennial goal is to “build a modern socialist country that is prosperous, strong, democratic, culturally advanced and harmonious" by 2049, at the centenary of the People's Republic of China. All the separate policy intentions, goals and targets in the upcoming 14th FYP, general and indicative as they may seem, are thought to bring China onto the next step to fulfil this second centennial goal. So, what do we know about the plan so far?

Economic growth to slow down

In an authoritative

article this September, which was profusely laudatory of

Xi Jinping, the chairman of the

NDRC and

Xi’s presumed ally, He Lifeng, noted that the main thrust of the 14th FYP is to let

Xi Jinping’s overall development constructs - innovation, macro-coordination, green development, opening up, and common sharing of wealth - inform all aspects of China’s future development in order to ensure more effective, more just, more sustainable, safer and higher quality development. In 2020, the Chinese government declined to provide an official growth target for the year due to the Covid19 crisis. However, after all, it would be a great surprise if there would not be an indicative growth rate in the new five-year plan. In this context, He Lifeng only provided an indication, as he noted that the New Normal was still a valid expectation and that there is a need for more reforms to push demand-side and market reforms. The New Normal indicates

growth rates averaging about 6-7% annually. China will also continue to open up its economy to the outside world, but still without sacrificing its own economic interests.

‘Inward pivot’ to ward off US containmentThe Covid19 crisis and the international backlash towards China, not least from the US, and the US trade war on China has

alerted China’s leadership of the need to secure adequate essential reserves of critical resources such as farm products, energy resources and minerals. To safeguard such supplies, the 14th FYP will make provisions for the increase of storage capacity for such resources to enhance China’s economic security.

In recent months,

Xi Jinping has added a new formula for the economy, called “dual circulation” to his already comprehensive arsenal of development constructs. The concept reveals real concerns about the relationship with the US and the mounting criticism of Chinese economic and trade practices around the world. The concept of “dual circulation” refers to what is termed an ‘inward pivot’ that will make China more self-reliant economically, if a substantial decoupling between China and the US should occur.

Says Jude Blanchette, Freeman Chair in China Studies at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington: “There’s greater urgency now that the U.S. not only controls the choke points, but has shown they are prepared to exert pressure on them, as we have seen with Huawei and

ZTE.” The “dual circulation” concept is thus a carefully designed gradualist decoupling strategy reflecting China’s response to US pressure.

Finally, a host of other issues relating to the economy, such as the strains on the financial sector, the relationship and balance between the state-owned and private enterprises, social welfare, and so on will be dealt with in the plan, but the concrete policy priorities and, even more, the policy initiatives have not been discussed in public as yet, beyond the very general statements put forward by top leaders. However, the plan will not present radically new ideas, but rather continue what has already been laid out in current key policy statements and programs. It is clear that the role of the

CPC in relation to the private business sector will be strengthened even more than it is now and that the

CPC clearly intends to be in charge of all economic issues. Finally, we must also presume that the 14th FYP will focus on accelerated job creation to help the

tens of millions of workers laid off during the Corona crisis as well as new entrants into the labour market, not least university graduates.

Carbon neutrality in 2060 – a green turn of the economy?In a

speech to the 75th General Assembly of the United Nations on September 23,

Xi Jinping argued for a green turn of the globe following the Covid19 crisis, and he made the surprise statement that: “We aim to have CO2 emissions peak before 2030 and achieve carbon neutrality before 2060.” The announcement came as a shocker without prior public debate in China. Therefore, it is reasonable to assume that it is a result of

internal deliberations based on inputs from a number of research projects on China’s future climate policy that were initiated to provide inputs to the 14th five-year plan.

The long term carbon neutrality announcement was favourably received around the world.

Said European Commission President, Ursula von der Leyen: “I welcome China’s ambition to curb emissions and achieve carbon neutrality by 2060”. In fact,

the top EU leadership had urged the Chinese leadership to formulate such a goal at the EU-China Summit immediately preceding Xi’s speech at the UN.

The carbon neutrality target is not yet part of China’s Nationally Determined Contributions [NDC] to the Paris Agreement, nor is it binding as it stands. However, it could still be a game-changer for the 14th FYP and make it the first really green FYP, since all other goals and targets will have to align behind it. This is especially true for the national energy plan that will be finalized next year on top of the 14th five-year plan. It must demonstrate a clear ambition to cut down on coal consumption, and

climate observers will pay critical attention to how that will be done over the next five years.

In fact, China’s coal-fired power plants are

running at about 50% of capacity only, and new capacity is not needed anymore. All the same, new projects are still approved and implemented, because of the importance of coal for local economies and conservative energy systems thinking. In the first half of 2020,

China approved 23 gigawatts worth of new coal power projects, more than the previous two years combined.

Right now China is responsible for about 28% of the world’s emissions of GHG, 90% of which comes from fossil fuels. China is the world’s biggest greenhouse gas [GHG] emitter, although historical and per capita emissions are still trailing far behind the US and the EU. But it is obviously necessary for China to act on its emissions more forcefully than before and the central government will have to tackle the root cause of the problem, i.e. the mandate to approve coal plants. This mandate was transferred from the central government to the provincial governments in 2012 which led to a flare of coal investments, since – as noted by

Carbon Brief - “China’s economic system is based on abundant and cheap capital being made available to the state-owned sector with little concern for economic viability, as long as the investments made are broadly aligned with the five-year plans.” Even more, the Covid19 crisis this year has even led to loosening of regulations for coal plant approval to reboot local economic development.

While China’s central government faces difficulty in controlling coal investments at home, it seems to be the same outside China.

It has been found that most Chinese deals in energy and transportation are locked in with traditional sectors and that they do not align with the low-carbon priorities of the NDCs of many of the receiving countries.

It has also been calculated that foreign power plants supported by Chinese financial institutions released almost 600 million tons of CO2 per year between 2001 and 2016 (more than all but seven countries in the world). This could move to 1 GT annually with current expansions. If these plants operate for 30 years on average, their lifetime CO2 emissions could amount to at least 18 Gt (roughly half of global emissions in 2017), although they generally employ the cleanest technology available in the world market.

Many of these investments have come under the hat of the

Belt and Road Initiative [

BRI]. Therefore, if he is to be taken seriously, Xi cannot allow his signature

BRI program to export Chinese emissions to other countries while he is making China a ‘greener island’.

A new direction under pressure

It appears that continued economic growth, economic security and a green economic turn will be top priorities in the 14th five-year plan. This is to happen at a time when China is under increasing international pressure for different reasons.

Often enough,

Xi Jinping has acknowledged that the international situation is complicated and that it challenges China in so many different ways. Next year in March, the final draft of the 14th FYP will spell out whether XI is able to stick to his promise to make China greener. It will require all his craftsmanship to align the different agendas against the overarching carbon neutrality goal. On 28 September, Xi chaired a

CPC Politbureau meeting that discussed the draft 14th five-year plan. The

press release from the meeting confirmed the general directions discussed above, but did not specifically mention the carbon neutrality goal or a green turn of the economy. Therefore, the devil is still hidden in the subsequent details, and there seems to be a need in China to process

Xi Jinping’s surprise announcement further before his green ambitions can take hold of the new five-year plan.

China’s new 14th five-year plan [FYP] covering the period from 2021 to 2025 is a key tool to attain the long term goals for China’s development. The final plan will only be disclosed at the annual session of the National People’s Congress [NPC] in March next. However, before then, the upcoming 5th plenary meeting of the Central Committee [CC] of the Chinese Communist Party [CPC], to be held in late October, will endorse the draft after having analyzed the current economic situation and the results of the 13th five-year plan.

China’s new 14th five-year plan [FYP] covering the period from 2021 to 2025 is a key tool to attain the long term goals for China’s development. The final plan will only be disclosed at the annual session of the National People’s Congress [NPC] in March next. However, before then, the upcoming 5th plenary meeting of the Central Committee [CC] of the Chinese Communist Party [CPC], to be held in late October, will endorse the draft after having analyzed the current economic situation and the results of the 13th five-year plan. Incidentally, this poverty alleviation effort also explains some of the Draconian policies to modernize Xinjiang and Tibet in recent years through forced internment of local “minorities”, indoctrination, skills upgrading and group transfer of rural surplus labour to industry and services.

Incidentally, this poverty alleviation effort also explains some of the Draconian policies to modernize Xinjiang and Tibet in recent years through forced internment of local “minorities”, indoctrination, skills upgrading and group transfer of rural surplus labour to industry and services.